Taryn Simon – The Innocent

During the summer of 2000, Simon worked for the New York Times Magazine photographing individuals who were wrongly convicted, imprisoned, then thankfully, freed from death row. Following the assignment, she applied for a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in Photography to travel across the United States to photograph and interview people who were wrongly convicted–in most cases–due to mistaken identity.

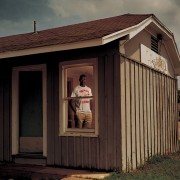

„I photographed each innocent person at a site that came to assume particular significance following his wrongful conviction: the scene of misidentification, the scene of arrest, the alibi location, or the scene of the crime. In the history of these legal cases, these locations have been assigned contradictory meanings. The scene of arrest marks the starting point of a reality that is based in fiction. The scene of the crime, for the wrongfully convicted, is at once arbitrary and crucial; a place that changed their lives forever, but to which they had never been. Photographing the wrongfully convicted in these environments brings to the surface the attenuated relationship between truth and fiction, and efficiency and injustice.“ ( Taryn Simon, MoCP)

Simon photographed these men at sites that had particular significance to their illegitimate conviction: the scene of misidentification, the scene of arrest, the scene of the crime, or the scene of the alibi. All of these locations have been assigned contradictory meanings for the subjects. The scene of arrest marks the starting point of a reality based in fiction. The scene of the crime is at once arbitrary and crucial: this place, to which they have never been, changed their lives forever. In these photographs Simon confronts photography’s ability to blur truth and fiction—an ambiguity that can have severe, even lethal consequences.

Simon says she noticed that photography itself played a role in several of the convictions. “Mistaken identifications are extremely influenced by photographs, or visual materials — composite sketches, photographs, lineups — and it’s relying on witness memory or the victim’s memory,” the photographer says. “That memory is not precise… all these men are testaments to that.”

In some cases the convictions were the result of police corruption, in others “just flat-out misidentification,” she says.

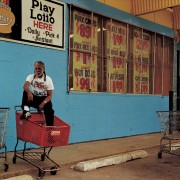

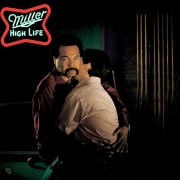

Frederick Daye is pictured at his “alibi location,” a bar stool at an American Legion Post in San Diego, where more than a dozen witnesses placed him at the time he was accused of raping and robbing a young woman. Daye tells that the police coerced the victim into believing he was her attacker by showing her his photo and telling her he was the man responsible. Daye says he’s grateful that he was eventually released after serving nearly 11 years for the 1984 crime. “I had no idea that I would ever get out of prison. I thank God… because if it wasn’t for the DNA test, I’d still be in prison right now.”

But he says the experience cost him his sanity and he’s lost jobs because of his prison record. Daye says he has been told he would soon receive compensation from the state of California for his wrongful imprisonment. But “if they were to give me $100 million, that still wouldn’t be enough. You can’t put a value on the loss of an individual day, minute, hour, whatever, in jail. You can’t get that time back.”

More works

Photo credit

1 und dann 1 und genau 2 und 3 genau